The National and Regional Partnerships (NRP) Fund and the end of the CAP two-pillar structure

The European Commission’s long-awaited proposal for the new Multiannual Financial Framework, which was unveiled in July this year, presents some major and comprehensive budgetary changes for the EU’s 2028-2034 spending cycle from. The most significant change for the EU’s farming budget is the proposal to merge the two existing pillars of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), traditionally known as ‘first pillar’ direct payments supporting farm income and stability and ‘second pillar’ payments focused on rural development measures, into one single funding instrument called the ‘European Fund for Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion, Agriculture and Rural, Fisheries and Maritime, Prosperity and Security’. Under this €865 billion, ‘National and Regional Partnerships’ Fund, agricultural subsidies would be merged with other funds (such as those covering cohesion policy and migration and border management) into a single system in which a minimum budget of €300 billion will have to be dedicated to European farmers. This would not only represent a substantial financial cut from the €386.6 billion allocated in the current CAP 2021-2027 budget but also set the stage for a significant overhaul of the governance model of the CAP (read more on this in our last blogpost).

Despite the abolishment of the CAP’s two-pillar structure and their integration into a larger fund, the EU’s new farming policy keeps its special status with a ring-fenced budget and separate, detailed proposal for a post-2027 CAP Regulation, further outlining specific CAP interventions and rules already set out in the NRP Regulation. What emerges in the Commission’s proposals is a clear (and hardly surprising) focus on simplification, competitiveness and increased spending flexibility for Member States (MS) in the upcoming CAP reform.

By contrast, robust regulatory targets and measures as well as earmarked funding for environmental and climate action are starkly absent.

The shift from Brussels ensuring mandatory environmental farming requirements towards giving more power to national capitals and making green measures and rules for farmers largely voluntary is not new1, however, it remains a cause for great concern. Although increased intensity and frequency of droughts, wildfires and floods in Europe are already wreaking havoc on agricultural landscapes and causing economic damage for farmers, the Commission’s proposed farming plans for 2028-2034 seem to give far less prominence to environment and climate action compared to the 2021-2027 CAP proposal, raising serious questions about whether the proposed structure of the new CAP is fit for purpose to achieve the EU’s sustainability goals.

Less ambitious green agricultural goals in the NRPF framework and new CAP regulation

The overall direction of travel of the post-2027 CAP is already clearly stated on the first page of the NRPF Regulation, calling for a “more targeted [CAP that] finds the right balance between incentives, investment and regulation and ensures that farmers have a fair and sufficient income.” While the current CAP regulation is built on 10 key policy goals (including three of them dedicated to climate change action, environmental care and the preservation of landscapes and biodiversity), specific objectives related to climate and the environment are not mentioned in the list of five specific objectives of the NRPF Regulation (see Article 3):

a. Support the Union’s sustainable prosperity across all regions

b. Support the Union’s defence capabilities and security across all regions

c. Strengthen social cohesion by supporting people and strengthening the Union’s societies and the Union’s social mode

d. Sustain the quality of life in the Union

e. Protect and strengthen fundamental rights, democracy, the rule of law and to uphold Union values

Climate and environmental policy goals related to the agriculture and forestry sector are only briefly mentioned as sub-objective in the NRPF Regulation.2 However, the draft CAP Regulation states more explicitly that “Member States should target support through NRP Plans towards CAP priorities, which are essential for the long-term sustainability of agriculture.” More specifically, the CAP post-2027 should:

▪ accelerate the transition towards more sustainable production methods, contributing to climate-neutrality objective by 2050;

▪ offer better rewards for delivering more ambitious ecosystem services which go beyond the results achieved through mandatory requirements;

▪ strike a new balance between a farm stewardship with a set of mandatory requirements, and agri-environmental and climate actions (AECA) which support commitments beneficial for the environment, climate and animal welfare and a transition towards more resilient production systems (more on farm stewardship and AECAs in the section below).

In addition, Article 4 of the proposed CAP regulation mandates Member States to provide support for farmers for at least six environment and climate priority areas, including “climate change adaptation and water resilience; climate change mitigation including carbon removals and on-farm renewable energy production, including biogas production; soil health; preservation of biodiversity, such as conservation of habitats or species, landscape features, reduction of use of pesticides; development of organic farming; animal health and welfare.“

However, a first analysis of the proposed NRPF framework and CAP Regulation suggest that the new climate and environmental policy objectives related to agriculture are too broad and are given very little priority (without being even mentioned as specific objectives in the NRPF Regulation) compared to the current CAP programming period. The absence of enforceable targets is a concerning omission given the scale of the environmental challenges facing the EU’s agri-food sector.

The new CAP’s Green Architecture: old tools but weaker?

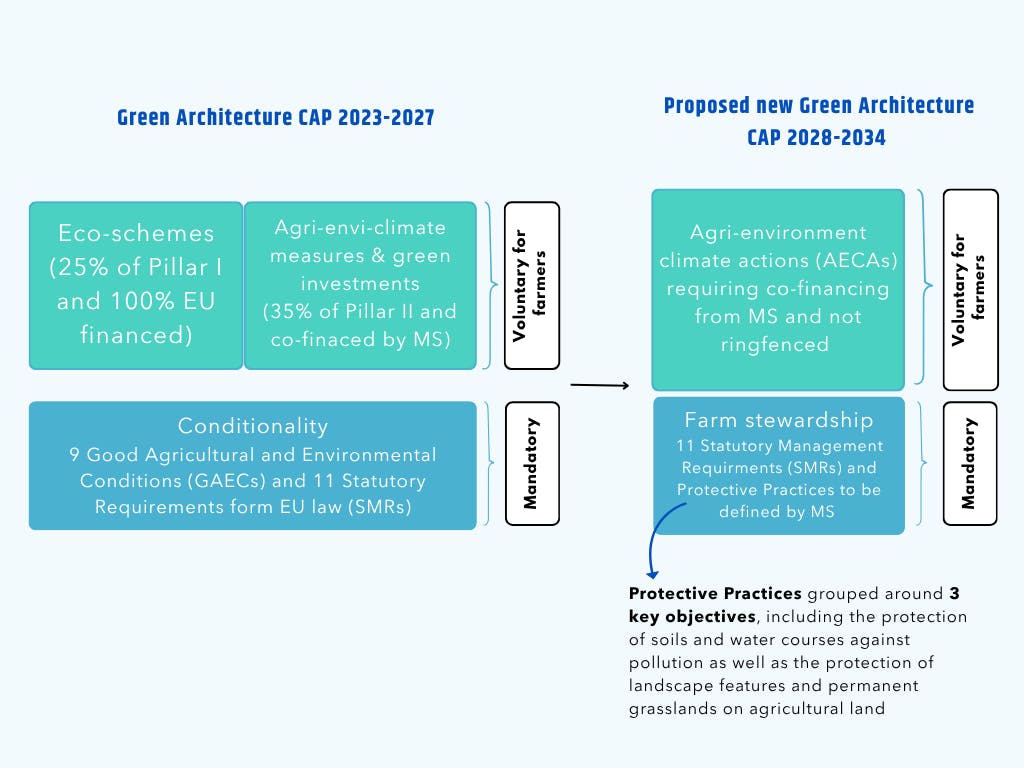

An important instrument to steer environmental protection and climate action in the farming sector is the CAP’s green architecture (provided it is well designed and implemented). In the current CAP, the green architecture is essentially relying on three layers: conditionality, eco-schemes, and agri-environment and climate measures (AECMs). Conditionality refers to mandatory baseline requirements, the so-called Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAECs) and Statutory Management Requirements (SMRs), which usually ensure that farmers receiving direct support comply with basic EU standards related to the environment and climate. In addition, farmers can receive payments for environmentally friendly farming through eco-schemes and AECMs which represent voluntary measures with the aim to incentivise farmers to use more sustainable farm and land management practices. Fully EU-funded eco-schemes and the obligation to ringfence 25% of the Pillar 1 budget for this instrument was one of the main novelties of the current CAP. AECMs are rural development measures which are co-financed by Member States and cover long-term environmental commitments with a required ringfencing of at least 35% of a country’s Pillar 2.

For the post-2027 CAP, the European Commission now introduced a revised, two-layer green architecture for environmental and climate action which is based on Farm Stewardship and Agri-Environment and Climate Actions (AECAs).

Compulsory and simplified Farm Stewardship regime essentially replaces the current conditionality system and sets baseline requirements all CAP beneficiaries have to comply with, including 11 Statutory Management Requirements (same as before) and Protective Practices which are similar to the current GAECs with the key difference that Member State would be given much wider discretion and flexibility in defining the specificities of these practices. After having already relaxed the current nine GAECs as part of the Commission’s CAP simplification packages.

The new rules on Protective Practices are even less detailed and prescriptive on how to deliver on “the protection of carbon-rich soils, landscape features, permanent grasslands, soil against erosion, and water courses and groundwater from pollution”, potentially risking a race to the bottom among Member States.

At the same time, the currently ring-fenced eco-schemes and AECMs would be merged into one instrument, the Agri-Environment and Climate Actions (AECAs). With no minimum spending requirements for these measures, Member States would have fewer incentives to allocate funding to climate and environmentally friendly farming practices. In addition, AECAs might become a less appealing option for Member States to prioritise in their NRPF plans since they require co-financing with national contributions of at least 30 %. As a reminder, current eco-schemes require no contributions from MS and are fully EU-funded whereas agri-environmental-climate measures require only a minimum of 20% contributions.

Last but not least, it is worth mentioning that the Commission has included Coupled Income Support (CIS), formerly voluntary for Member States, in the list of mandatory CAP interventions. CIS has often been criticised for being a production-distorting form of subsidy, with progressively weaker regulations, that incentivises the intensification of the livestock sector with negative impacts for our climate and environment (Matthews, 2020; Baldock et al., 2024).

Nevertheless, the proposed CAP regulation is making CIS a mandatory intervention for Member States for the first time, whilst allowing them to allocate more CAP funding (20% instead of 13%) for this support measure, thereby potentially creating competition for funds within the CAP budget and sidelining more targeted environmental and climate schemes.

While Member States "shall take into account environmental impacts” of coupled payments to the livestock sectors, the specific method for doing so is not strictly mandated, however, the text suggests they could do so by “setting a maximum livestock density criteria in nitrate vulnerable zones.”

A few straws of hope

Despite the above-mentioned concerns and overall shift from mandatory environmental requirements to voluntary incentives for farmers, there are some positive elements that could still encourage environmental and climate action under the new CAP and NRPF Regulation.

For instance, Member States can support farmers’ "voluntary transition towards resilient production systems [...] through farmer-drawn action plans”, incentivising a more holistic shift in farming practices rather than just encouraging farmers to implement individual measures.

The introduction of degressivity and capping, two mechanisms aimed at distributing direct payments to farmers more fairly, is another positive element proposed for the next CAP.

While degressivity would ensure that direct payments to farmers decrease as the total payment amount increases, capping would mandate that the total amount of area-based income support for any single recipient is capped at a maximum of €100,000 per farmer per year.

It is also worth mentioning that the entire NRP Fund has a horizontal climate mainstreaming target requiring 43% of its spending to be linked to climate and environmental goals. As Agri-Environment and Climate Actions would count 100% towards this target, uptake and demand of these measures could potentially increase in order to help Member States to meet the overall goal.

Lastly, the Commission holds significant power in overseeing and guiding the development of Member States' NRPF Plans, which it should use to make recommendations with regard to agriculture and ensure environmental and climate measures under the new CAP are robust, ambitious and adequately funded.